EN Leben Intro

The most impressive and to-the-point statements about Christine Nöstlinger’s books, viewpoints and her life are those she made herself. In this biography we thus chose to give the floor to Christine Nöstlinger as much as possible. The text is mostly based on passages and quotes from her book „Glück ist was für Augenblicke“, published in 2013 by Residenzverlag.

EN Leben Block1

“The term ‘happy childhood’ does not really speak to me. I can only say that during my childhood, I’ve experienced the most intense moments of happiness, as well as the most intense moments of sadness that I’ve ever known.“

(Stockholmer speech, 2003, on the occasion of receiving the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Awards)

Photo: Christine at the age of 2 with her mother

EN Leben Block 2

Christine is born on the 13th of October 1936 and grows up in the 17th district of Vienna, named ‘Hernals’, together with her parents, grandparents and her five years older sister Lisl.

It has been stated quite often that she and her family were part of the ‘Hernalser’ working class. This statement is true for the neighbourhood she grew up in, but not really for her own family as her mother was a kindergarten teacher and her father a watchmaker.

“In the first three years of my life my father looked after me; like many others he was unemployed. He took care of me during the night, even though my mother was at home, this was due to the disagreements between my parents about how to bring up children; my dad didn’t like diapers at all … I slept without them. And when I wet my sheets, I sneaked into his bed and slept there … Of course I cannot clearly remember this, but every time she [my mother] told me this story, I started to feel warm and blissful from the inside.”

The father is leaving

In 1936, Austrofascism rules over Austria. Christine is two years old when Hitler is cheerfully welcomed into Austria and invades the country. She is three years old when the Second World War starts.

Her dad is sent to Poland as a soldier in 1939.

She loves her dad unconditionally. The relationship with her mother is more ambivalent. In the eyes of her mother, Christine is a wild and angry child, at least wilder and naughtier than others. However, this has less to do with her personality than with her education. In Christine’s family (physical) punishments do not exist.

EN Der Vater muss fort 2

“…I cannot remember it. I do recall however, how he stood in front of our door before he left, right after his marriage, dressed in the uniform with his steel helmet and riffle. When I reflect about sad images that I have collected during the years, this for sure is one of the saddest.”

Quote from: Glück ist was für Augenblicke

Photo: Christine's father as soldier

A political family

In this socialist family, politics are often and openly discussed. Christine already knows during her years in primary school who is understood to be a Nazi-, a communist- or a socialist child. The fact that her uncle (the brother of her mother) is a Nazi and a high SS official leads to family tensions, which is being argued about openly:

“One day, in the middle of the war, when he [the uncle] came to visit us in his SS uniform, he told my mother: ‘…the Jews are all going through the chimney!’ My mother jumped up and slapped him in the face. I was imagining how it would look when people went through a chimney. Later I saw it … in one of Chagall’s paintings. An angel floating above a little house.”

The resistant mother

Christine’s mother refuses to support the Nazi way of education in her kindergarten class. By doing so, she has to face a disciplinary procedure and several Gestapo interrogations. In 1943, she is sent to early retirement. Christine thus learns first-hand what civil resistance means.

In 2015, she describes the way she experienced these events as a child, in a commemorative speech on the occasion of the 70th anniversary of the Mauthausen concentration camp’s liberation:

“One of the only Jews who lived in our neighbourhood was mister Fischl … my mother spoke about him quite often. She had seen …, a couple of days after the German invasion, how a horde of SA men first forced Mr. Fischl to clean an anti-Nazi slogan off the sidewalk with a toothbrush, and how they afterwards carried him away on a truck.

And every time she told us: ‘If I didn’t have you children, I would have intervened, and would have gotten mister Fischl out of there.’

I was young and believed that my mother would have saved him, therefore, somehow, I felt guilty that mister Fischl ended up in a concentration camp“

Maikäfer flieg ("Fly away home")

For Christine, now an elementary school child, wartime is her day-to-day reality: she knows the terror of the Nazi regime, the fear of bombs, the long and fearful hours in the bomb shelter. She describes this period in her life, impressively, in her novel “Maikäfer flieg”, which was turned into a movie in 2016: the return of her father who had deserted heavily wounded from the army in 1944 and therefore had to hide from the Nazis, the invasion of Russian troops in Vienna, and the long awaited end of World War II.

Photo: © Kranzelbinder Film 2016

EN 1945 Poppel Folgeblock

“For me, the war was over when we could move back to our home, during summer … I had known war well, I knew how to handle war. Peace, on the other hand, I still had to get familiar with.“

Christine recounts in “Zwei Wochen im Mai” (1988) how peace, first, had to be learned. The family is poor. Her father is unemployed, her mother has been sent to early retirement. Her friends from elementary school are all attending a local secondary school, while Christine – as her big sister before her – is sent to a high school where she has to study Latin. Her sister is known as a perfect student, often complimented by her teachers, but not a role model for Christine. Her first years in high school are a confrontation with social differences. All of a sudden she’s different, she has to make friends with girls from the upper class and has to make up for her lost school years during the war.

“I couldn’t speak standard German at all, but in high school I had to speak ‘beautifully’. Therefore I didn’t speak, even not when I knew the answer, because I had to translate every sentence from dialect into the foreign language ‘beautiful’. My first grades were very bad ...“

EN Große Autoren

Christine remembers her school days:

“I do not recall any indications of me becoming a writer, even when looking back now. My essays were badly graded, what I wrote did not please the esteemed Mrs. Professor ... but this did not bother me at all. A bad grade on a math test would have disturbed me more. A bad note for writing made me incredibly proud, it showed that I dared to do something courageous …”

Quote from: Christine Nöstlinger. Die Buchstabenfabrikantin

Christine starts to gain interest in literature. She reads everything that comes on her path. She loves Erich Kästner, for example “Pünktchen und Anton” or “Fabian”, for whom she wishes a better ending – which she then makes up herself. She starts to feel better in high school during the second half of her education (1951). The shame she first felt about the fact that she came from a lower class compared with her classmates, gives way to a political consciousness targeting inequality. During these times she also develops close friendships with her best friends Poldi and Andi. Christine about her best friends:

“A Jewish child, a Nazi child and a socialist child, that wasn’t a bad mix.”

EN bio 1954 - 1969 erster block

Christine graduates in 1954 and is immediately accepted to the arts academy. In high school she was known for her drawing talent. Supported by a scholarship, she starts to study graphic arts.

Tucholsky helps

Her worldview is nevertheless mainly shaped through literature. Kurt Tucholsky, Brecht, Ringelnatz, Kästner and others become her favourite authors. She starts to see the world through “Tucholsky glasses”.

“… and over half a century later, I still think that he doesn't offer the worst guidance while observing our world, no matter if it’s about politics, friendship or love.”

To draw a galloping horse (viewed from in front)

In art academy, Christine gets to know people who – according to her own idea – are way more talented, so she starts to see herself as mediocre. Gradually she loses her motivation and interest in studying. After two years at the academy, she gives up and takes on a job at a Viennese newspaper publisher.

Failing

At the age of 21, she gets to know Peter. With this beautiful man – an all-round talent who fears reality and emotional attachment – she happens to find her big love which does not last long. In 1957, the couple decides to get married, as Christine became pregnant. She loses her child right after birth. She recalls this traumatic event many years later:

“My first child died when it was two-three-or-four days old. I don’t remember it clearly. For delivering, I needed two-three-or-four days. I don’t remember this either, and it makes no sense for me to try. It’s impossible. Not that I don’t want to, I just can’t. Only irrelevant things come up …”

(Quote from: Christine Nöstlinger “Ein vollgepackter Rucksack“. Einführung zu: B. Wimmer-Puchinger: Schwangerschaft als Krise. Springer Verlag, 1992; S. 10)

The child trap

In 1959, her first daughter Barbara is born. Christine and Peter get divorced by mutual consent, Christine moves back to her parents. No big conflicts took place, but they do not have much in common either, and especially, no common future seems to exist.

“There was this feeling: I’m trapped. I’ve surrendered to a man. To a child. To the conditions of the petty-bourgeois society. And then: the man who procreated this child does not want it. He pretends I’ve trapped him. There are thus two people trapped at the same time, blaming each other. But his trap is more comfortable, with better perspectives and more space to move around. Either way, we are not experiencing the same trap.”

Quote from: “Ein vollgepackter Rucksack“

A great intellectual, and a funny one

In 1961, Christine falls in love with Ernstl. His friends call him Nö, a student in journalism. He’s funny, educated and intellectual; that’s how she recalls him in her autobiography. She spends a lot of time with him at intellectual discussion circles in Viennese cafes, where they talk about politics, philosophy, literature and great societal utopias.

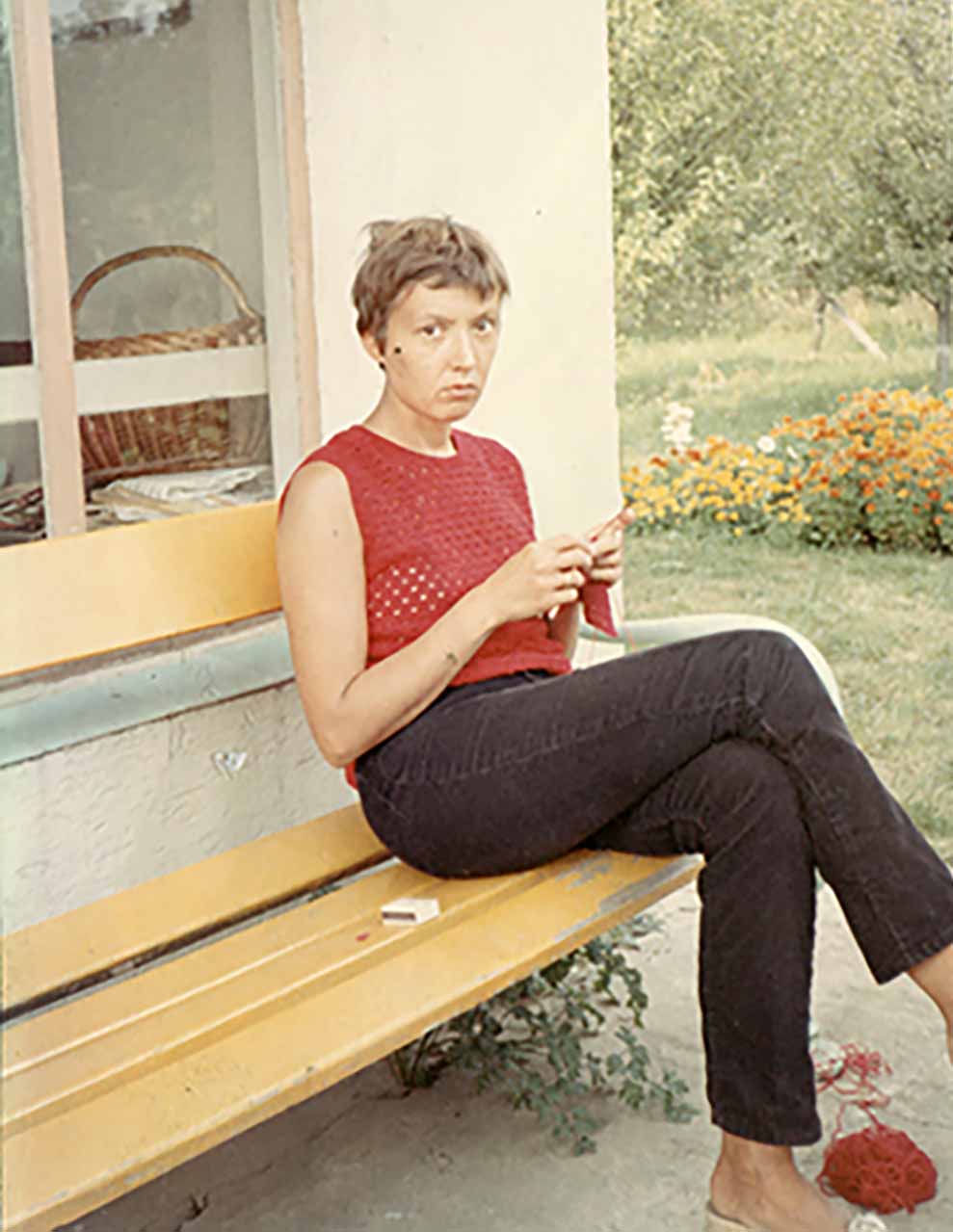

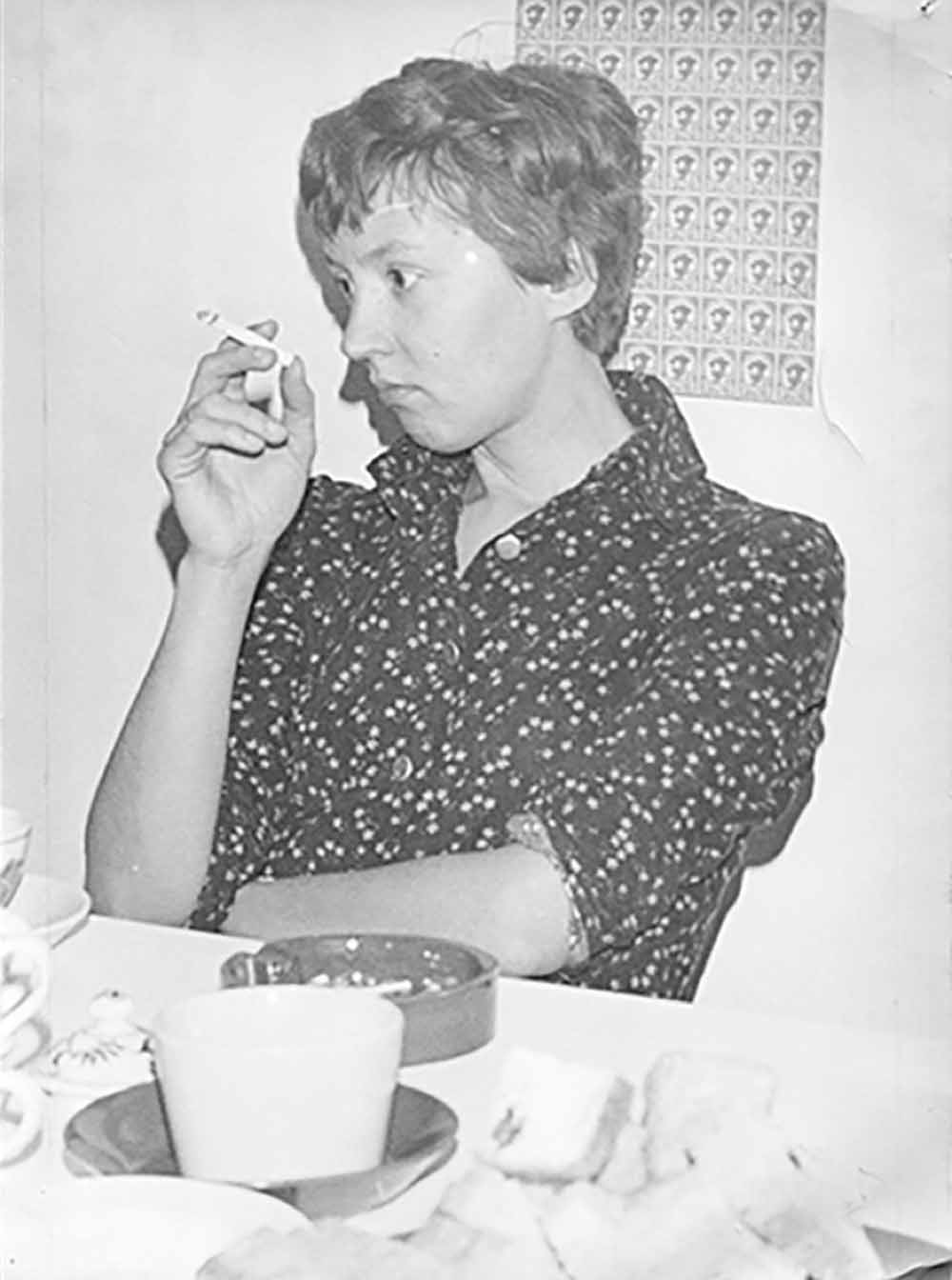

Photo: Christine in discussion

Now, housewife

Soon Christine becomes pregnant again, unplanned as before. Apart from condoms or the calculation of fertile days, no trustworthy method of contraception exists. Now, her second child Christiana, is born. As one still should marry in the case of pregnancy, Christine Draxler becomes Christine Nöstlinger.

“The civil servants did everything by hand at the time. The registrar crossed out ‘Draxler’ and replaced it with ‘Nöstlinger’, which I didn’t like at all ... he also took out a thick ruler and crossed out ‘student’ while replacing it with ‘housewife’.

That was a shock to me ... I never wanted to become a housewife, and now it was official, dark blue ink on pale pink paper.”

While men discuss things thoughtfully, women cook

Childbearing, emancipation, and gender patterns later become constant themes in her stories. Christine, a young mother of two, is reflecting about gender themes and discourse in her daily life, as it used to be practiced and discussed during the early 60s:

“I did not know a woman my age who deliberately chose to become a housewife. Everyone wanted to go to work and have a job. The satisfied housewives were only part of our mothers’ and mothers-in-law’s generation ...”

It can’t go on like this

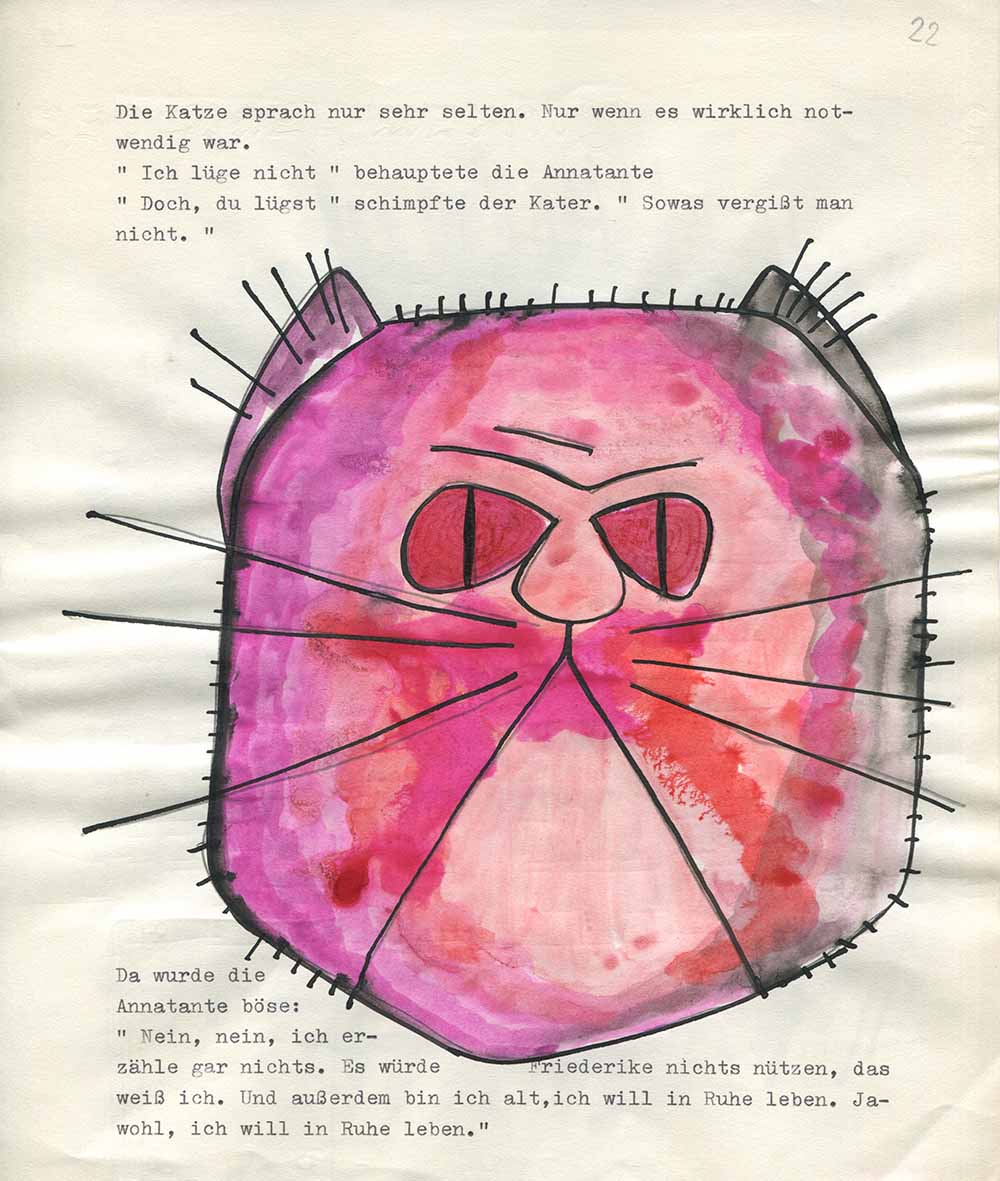

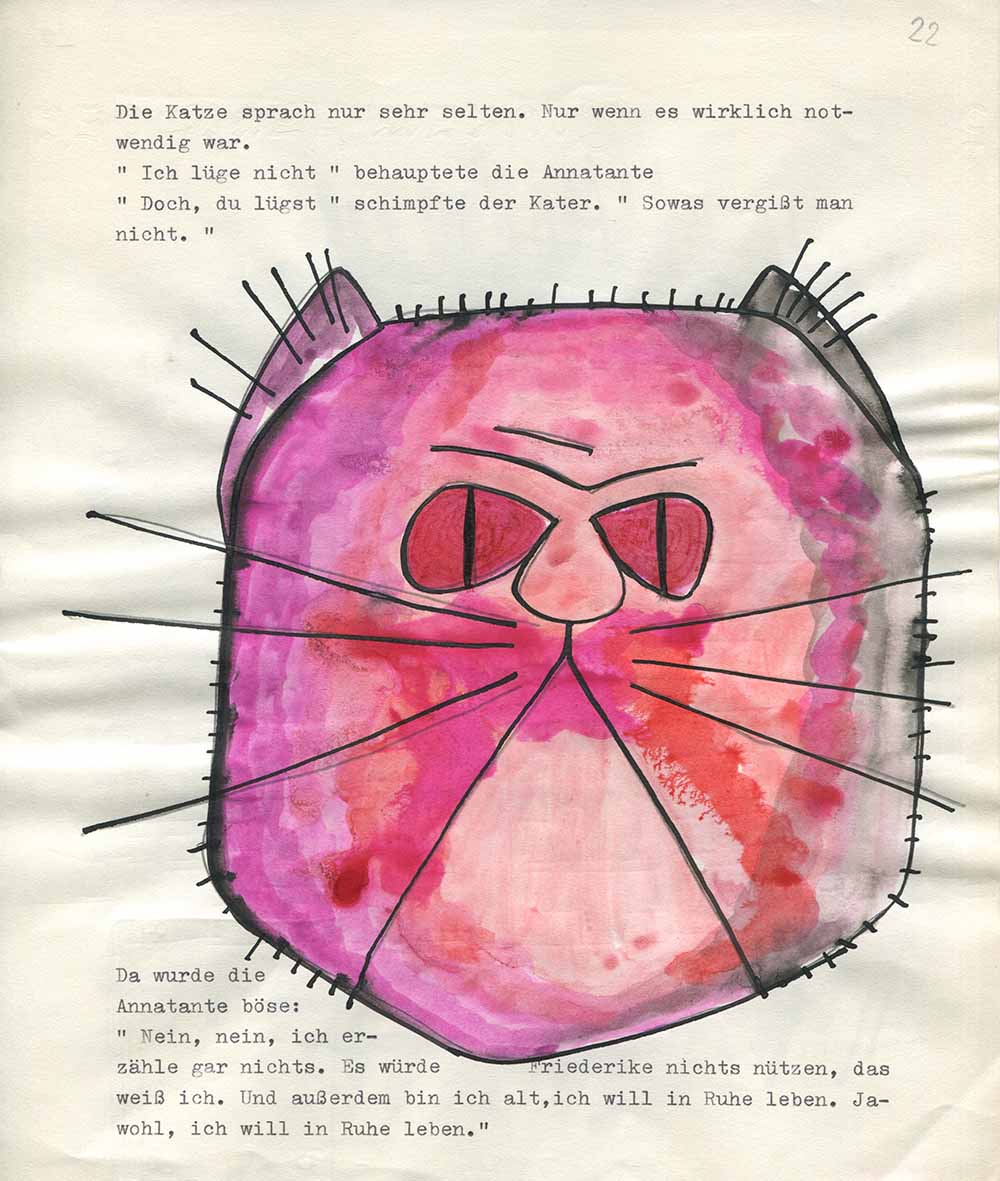

As a housewife, she becomes increasingly bored. Drawing and writing become her way to cope with the daily frustrations of leading a housewife’s existence. That is how her first book was created in 1968: the Feuerrote Frederike (“Fiery Frederica”). It takes her over one year to create, draw and write the piece. And, finally, it becomes – in its original form – accepted by the publisher “Jugend & Volk”, without yet being printed.

Friederike

With her first book Fiery Fredrica she succeeds to launch a new movement in the Austrian children's and youth literature. At least, people have often portrayed the book as such, which is now renown as a classic in children's literature. The central theme of this story is “mobbing”. While the term itself did not yet exist, children were always confronted with violence, exclusion and discrimination. Such a child is the main character of the book, chubby Frederica with ginger hair possessing a super power to resist violence in all its forms. The book became an immediate success.

EN Friederike 2

Christine about the development of this book:

“In my head, the story was long finished, as well as ’the story behind the story’. I knew this from the uncountable evenings I had spent with smart men who talked about literature. A story … has to have two dimensions. The second dimension of my story was the utopia of a land in which all people are free and equal, and thus happy.”

From educational work towards children's literature

The wind of the 68-movement is finally blowing in Austria. In children's literature, the questioning of the existing patterns of thinking and the child as an autonomous subject come to the forefront. Christine’s books represent these values as no others in Austria do at the time. By then, everything starts to go very fast. She gets invited for lectures about children’s literature, which she happily accepts. She writes during every free moment she has. And that’s how she succeeds in turning her life around. With the help of her mother, who supports her in taking care of the children, she becomes a full-time writer instead of a full-time housewife.

When Fiery Frederica is finally published in 1970, she has already finished two new manuscripts: “Die Kinder aus dem Kinderkeller” and “Mr. Bats Meisterstück”.

The first award

In 1972, she receives her first award, the “Friedrich Bödecker Preis”, which is awarded to authors who contribute to the development of children's and youth literature. Christine receives this award for five children's novels, which she has written by then (Feuerrote Friederike, Die Kinder aus dem Kinderkeller, Mr. Bats Meisterstück, Die drei Posträuber and Wir pfeifen auf den Gurkenkönig). Her typical and unconventional way of storytelling, which is funny and trenched with Viennese dialect, becomes unmistakably connected to her person. The award does not only reward her work in a literary sense, it also acknowledges that it promotes social phantasy and critical distance (Bödecker, 2004).

That very first award was thus given to her for her storytelling, not for her images, even though she had illustrated two of these books herself as a professional graphic artist. Now, at the latest, she is known in Germany and Austria as an established author of children’s books. At the prize-giving event in Hannover, Christine gets to know the German publishing scene for children’s literature, which forms the starting point for her international career. In the next years, every prize that a German-writing children's author could be awarded for, will follow.

Source: Bödecker, H., Bödecker, I., & Somplatzki, H.

(2004). Autorenbegegnungen: 50 Jahre Leseförderung durch den Friedrich-Bödecker-Kreis. Königshausen & Neumann.

Not a housewife state-of-mind

At home, in Vienna, she takes care of her two school-aged children and her husband, who works as a hotel porter but, nevertheless, sees himself as an author as well. However, the role of being a housewife still belongs to her.

“In reality, I did not care a lot. The greatest part of my brain was constantly occupied with forming sentences. It did not only happen when I sat down with my pen and lined notebook or in front of my green Olivetti. I was crafting sentences when I cut onions or stirred my Gulash, when I repaired the zip of trousers or went grocery shopping, when I cleaned the toilet or vacuumed the house.”

The inner child

Christine has close friendships with most of her publishers (Oettinger, Beltz und Gelberg, Jugend & Volk) and provides them with at least two or three books a year.

The stories that originate during these times are entrenched with phantasy elements, which she connects to realistic descriptions of the child’s interior world. The child that is the subject of her inspiration is her own inner child. The memories of her own childhood form the cornerstones of her storytelling. She only writes about things she knows of.

“The memory may be false as people don’t remember themselves objectively, but I never assumed to have known my own children. Or my grandchildren. I imagine things about them, I expect things from them. But the only child, who I believe to to really have known, is me when I was a child.”

Source: Gespräch mit Ute Wegmann anlässlich des 80. Geburtsttags der Autorin

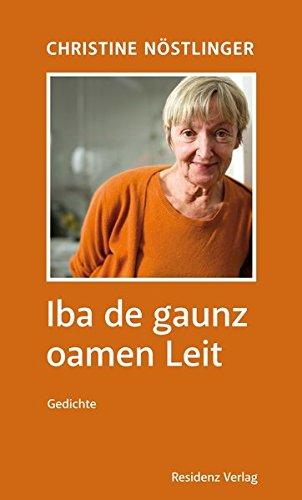

Dialect

In 1974, the first volume of her dialect poetry for adults was published (Iba de gaunz oaman Kinda). It gave her pleasure to write for adults in the language of her childhood. In Viennese dialect she describes a sad social reality, which even she herself would not confront children with. The poems are successfully broadcasted on radio shows and soon the first book is published. More poetry volumes soon follow (Iba de gaunz oaman Fraun in 1976 and Iba de gaunz oaman Mauna in 1987).

The family changes

Christine is a successful author and therefore her income as well as the family dynamics change. Her children – teenagers now – become more independent, Nö is able to quit his hotel job due to Christine being the main earner and he finally becomes active as a freelance radio journalist. The family buys and renovates an ancient farmhouse in a remote region in Lower Austria, the Waldviertel. It becomes a second home and in some periods a retreat for the Nöstlingers.

Foto: Christine, Ernst und Christine's mother playing cards

Konrad

In 1975, she writes another children's book in the tradition of phantastic children's literature: Konrad oder Das Kind aus Der Konservenbüchse (“The factory boy”). It tells about expectations parents have towards their children, friendships and being different. “The factory boy” becomes one of her most well-known books, and is the book probably most often used for adaptations among her stories. It was produced as a radio play, movie, theatre and child opera on international stages, such as Zürich’s opera house.

The dad, how sad….

In her personal life, 1975 is a sad year: her beloved father dies unexpectedly and suddenly at home. He dies in his sleep, her mother finds him in the morning, but she cannot understand what happened and calls Christine for help. It is a sad goodbye.

“And when I put the black socks on this tin and tall … man, who had become something like my life mentor, I finally started to cry, and I cried, until the undertakers knocked on our door.”

Quote from: Glück ist was für Augenblicke

Photo: Christine and her dad, around the year 1953

Dschi Dsche-i Wischer Dschunior

1979 was the UN year of the child. Children and their needs should be given more attention worldwide. For this occasion, Christine creates “Dschi Dsche-i Wischer Dschunior”, an art figure, whose experiences become narrated in a radio play which is broadcasted every school-day in Austria. As child and teenage advisor, the “Wischer” helps a whole generation of children and adults to cope with their early morning frustrations.

In 1980, when the “Wischer-letters” (the daily stories of Dschi Dsche-i Wischer Dschunior) are published as a book, Die Zeit writes:

“…with her ‘Wischer’ creation, Christine Nöstlinger has developed a new format for children's literature, which has not existed until now. It’s not that people haven’t played with language before, it’s not that human-like creatures have not taken the place of humans before. But here something happened, something that avoids an idyllic ideal, which is so externally different, nevertheless feels like it is amongst us.“

Source: www.zeit.de/1980/02/die-aus-lese

Listening, understanding, and comfort food

As a mother Christine lets her children Barbara and Christiana be free in every imaginable form, although she is always there when needed. Because of her empathy and generosity she becomes a “second mom” for many of her children’s friends. In the Nöstlinger home everybody is always welcomed. Sausage sandwiches, Schnitzel or Kaiserschmarren are prepared and served at any moment imaginable. Moreover, she gives advice when it comes to career wishes, study problems, politics and broken hearts. The same goes for her own friends, she always listens to the sorrows of others. These problems usually are discussed during dinner, when Christine celebrates her cooking skills. Her Viennese Schnitzel, her chocolate roulade “Brigitte” and her midnight Gulash are known to be legendary.

In 1993, her cook book Mit zwei linken Kochlöffeln is published. In 1996, a cook book for men, who either cannot or do not like to cook is published: Ein Hund kam in die Küche, and in 2003, Küchen-ABC.

EN Buchstabenfabrikantin

“I want to connect with people, otherwise writing is no fun.”

In the eighties, Christine develops a strong eagerness to work. She constantly produces new work and describes herself, ironically, as a one-woman-letter-factory. She defines writing as a craftwork, to be delivered in its highest possible quality. Novels, stories, poems, and pieces for radio, television and newspapers.

Source: Sabine Fuchs: Christine Nöstlinger. Eine Werkmonographie. Dachs Verlag. S. 24

The Hans-Christian-Andersen award

In 1984, she gets honoured with the Hans Christian Andersen medal for her complete published work. At that time, the award is regarded as the most important prize in children's and youth literature. Having received this one, Christine joins the line of famous writers and role models such as Astrid Lindgren (1958) and Erich Kästner (1960).

Novels

In contrast to her earlier stories, which were equipped with phantastic elements, Christine now invents figures that experience real problems in real life situations. She writes novels for children and adolescents, many of them describe problems – such as parents’ divorce – from a child’s perspective.

Franz and Mini

However, there are also the stories of Franz (“Hello Fred”, 1984), who has three big problems: being too small for his age, looking like a girl because of his blond curly hair, and his voice becomes squeaky especially when he is excited. The Franz (“Fred”) series covers 16 volumes, of which the last one appeared in 2011.

In 1992, she invents Mini, a long thin girl with red hair. Mini experiences daily challenges which children can relate to: the first day of school, her first love affair, holidays. The mini-series contains 16 volumes, of which the last one was published in 2007.

EN Franz und Mini 2

At first glance, these series appear to be less demanding than Christine’s previous novels. The Austrian “Presse”, however, wrote about them:

“Who … wants to understand the true art behind the Mini books (and also those of Franz!), has to hand them to children who just are about to learn reading fluently. Because each and every sentence is built in such a way that it can become grasped easily, no word can be found a pupil could stumble over. The length of these sentences is optimal, the stories are based on children’s daily realities. And most of all: There are a lot of books! Therefore, an advice to all parents: Don’t read the stories of Mini and Franz to your children … wait, and let your children discover Nöstlinger’s stories by themselves. ‘Der Spatz in der Hand’ and ‘Rosa Riedl Schutzgespenst’ will follow later.“

Quelle: Interview in the Presse by Katrin Nussmayr on the 25th of September 2019

Newspaper columns

Christine writes daily and weekly columns for various newspapers. Some criticise her decision to write for tabloids like “Die Ganze Woche" or “Täglich Alles”. She argues, however, that writing columns for these magazines enables her to reach people who rarely or never read books. And she wants to interfere in politics to counteract the already noticeable political shift to the right.

“When you’ve put that as your goal, it is self-evident to write for a news outlet that has many readers. The more, the better. You don’t have to look for elite newspapers anymore … my work ethos is not to impress the high civil servants, so that they nod approvingly. To me it’s more important that workers, sales(wo)men, farmers and caretakers understand me.”

Source: Sabine Fuchs: Christine Nöstlinger. Eine Werkmonographie. Dachs Verlag. S. 26

No one’s little girl anymore

Writing a column daily and delivering it on time is challenging and brings stress. On the side, she also writes books. Her daughters are adults now, but the role patterns between her and her mother are upside down. Her mother suffers from increasing health problems and therefore she needs to be cared for.

Christine's mother dies in 1987. She has always spent the summers with Christine and Nö in their house in the countryside. When she breaks down one night, the ambulance brings her to the intensive care unit. After three weeks in coma, she dies.

“The doctors told me that she didn’t see anything, didn’t hear anything, and didn’t feel anything. I trusted the doctors, but while standing next to her bed, I also believed that she looked at me angry, because I didn’t let her die in her own bed.

To have no parents, I had to get used to that. Now, I was nobody’s little girl anymore.”

Source: Glück ist was für Augenblicke

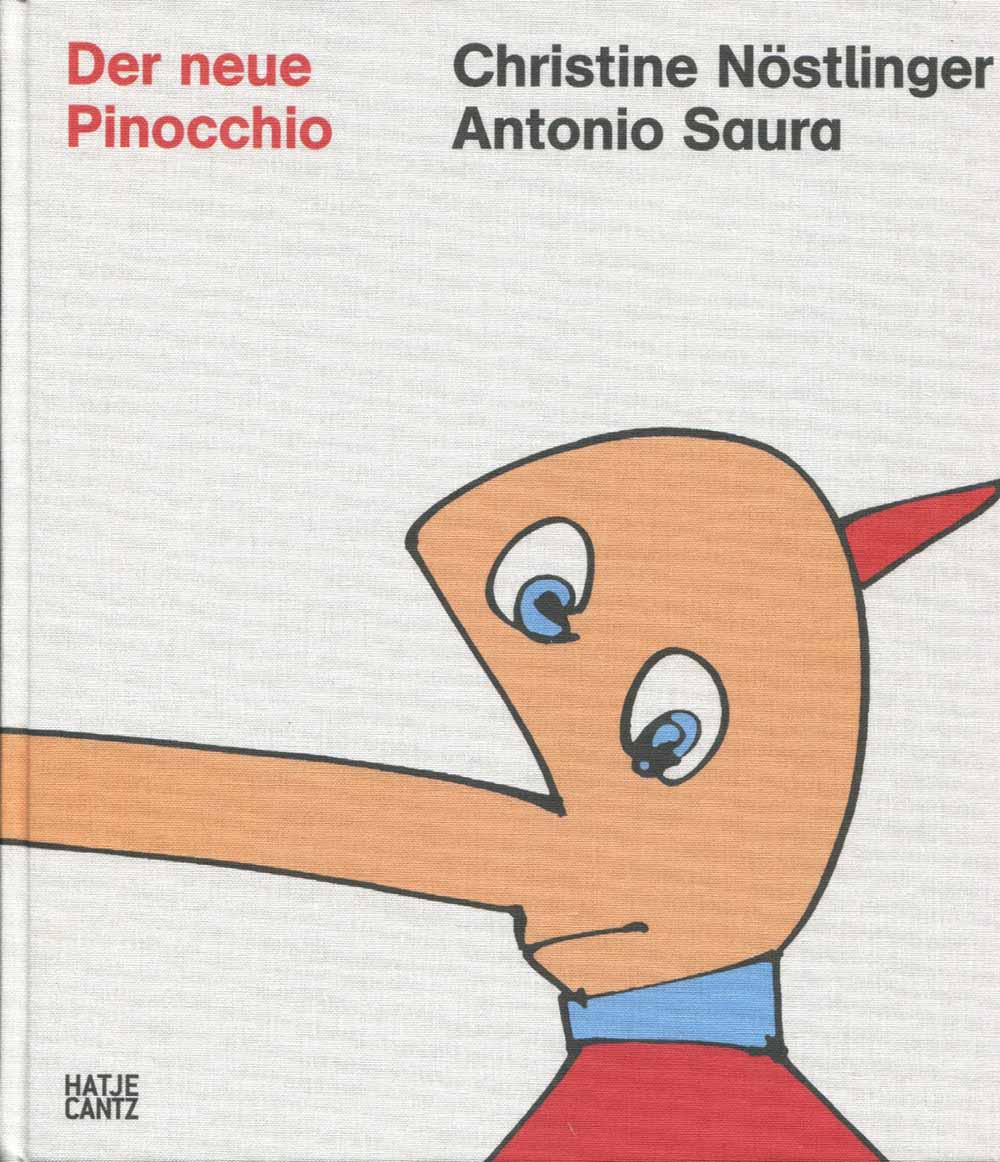

Pinocchio

In 1988, Der Neue Pinocchio (“The new Pinocchio”) is published, a collaboration with the Spanish artist Carlos Saura. Christine’s idea is to edit a classic children’s book, so that it can be understood and read by children. When reading Pinocchio and observing the illustrations, one should have fun: whenever you think Pinocchio is about to end well, something unexpected happens. In 1994, the book was awarded the label "Art Book of the Year” in Spain.

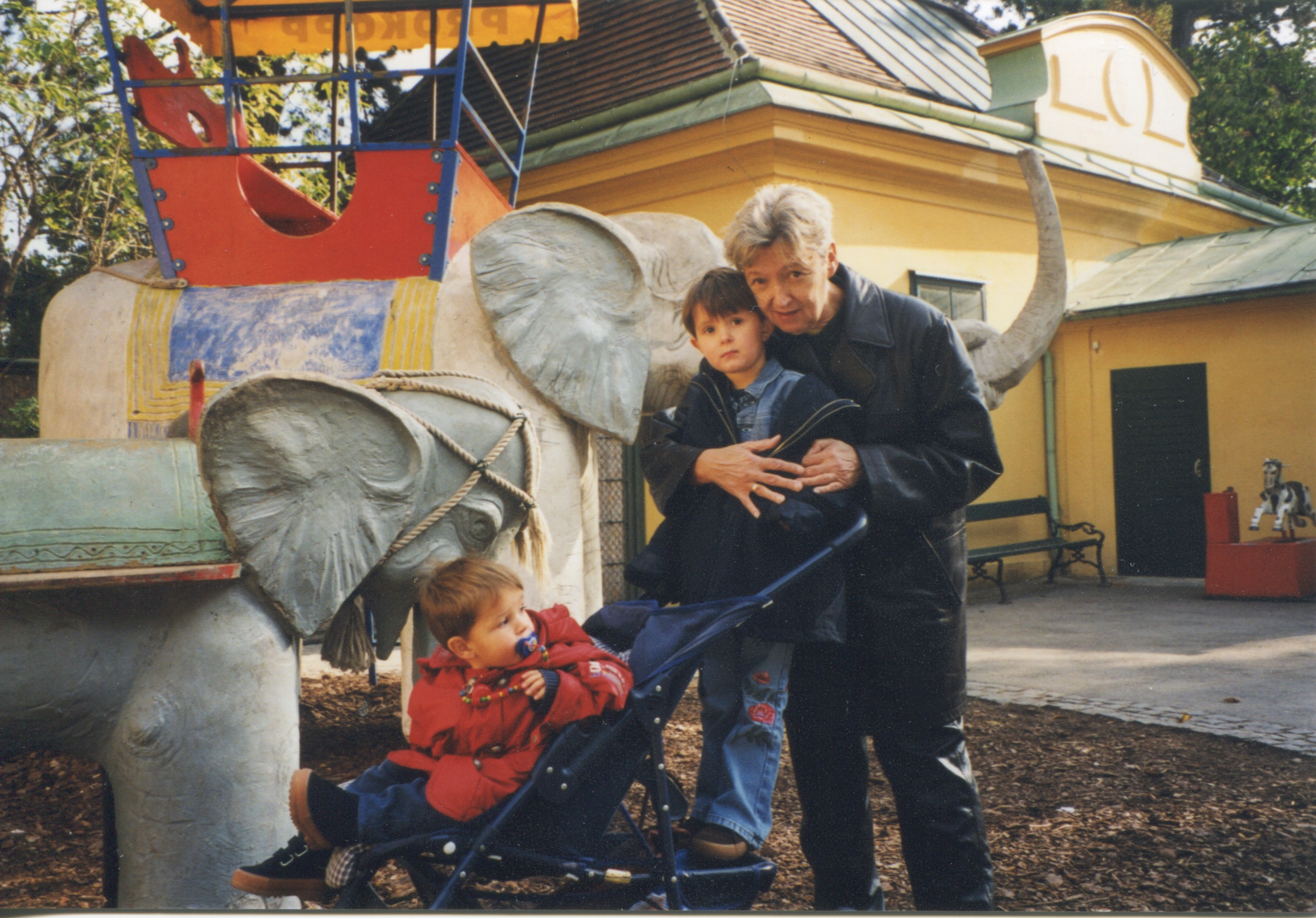

Becoming a grandmother

In 1995, Christine becomes a grandmother. Her daughter Christiana and her son-in-law Patrick have their first daughter Nette, and two years later, a son, Nando. Although the family lives in Konstanz, a spontaneous and loving relationship between the two children and their grandmother develops. In the following years, the children regularly spend one month during summer holidays at their grandparents family house in the Austrian countryside of Waldviertel.

To finally produce less

When it comes to private life, this is a time in which Christine is able to enjoy life. She enjoys her success and that she now works less, or that she just works on the things she appreciates. She likes to invite friends for dinner and cook for them, she enjoys traveling, she loves South Tyrol, and Italy for sure.

But she also likes to sit in the garden of her house in Waldviertel on warm days, enjoying the sunshine, and being happy when there are strawberries or fresh spinach in the vegetable garden.

She travels to see her daughter and grandchildren when she feels like it.

Christine is also socially engaged, from 1997 to 1999 she acts as the chairwoman of “SOS Mitmensch” where she sticks up for refugee- and human rights.

Nö, on the other hand, is kind of withdrawing into his inner self during these years, he suffers from a depression, which does not improve in spite of various therapies.

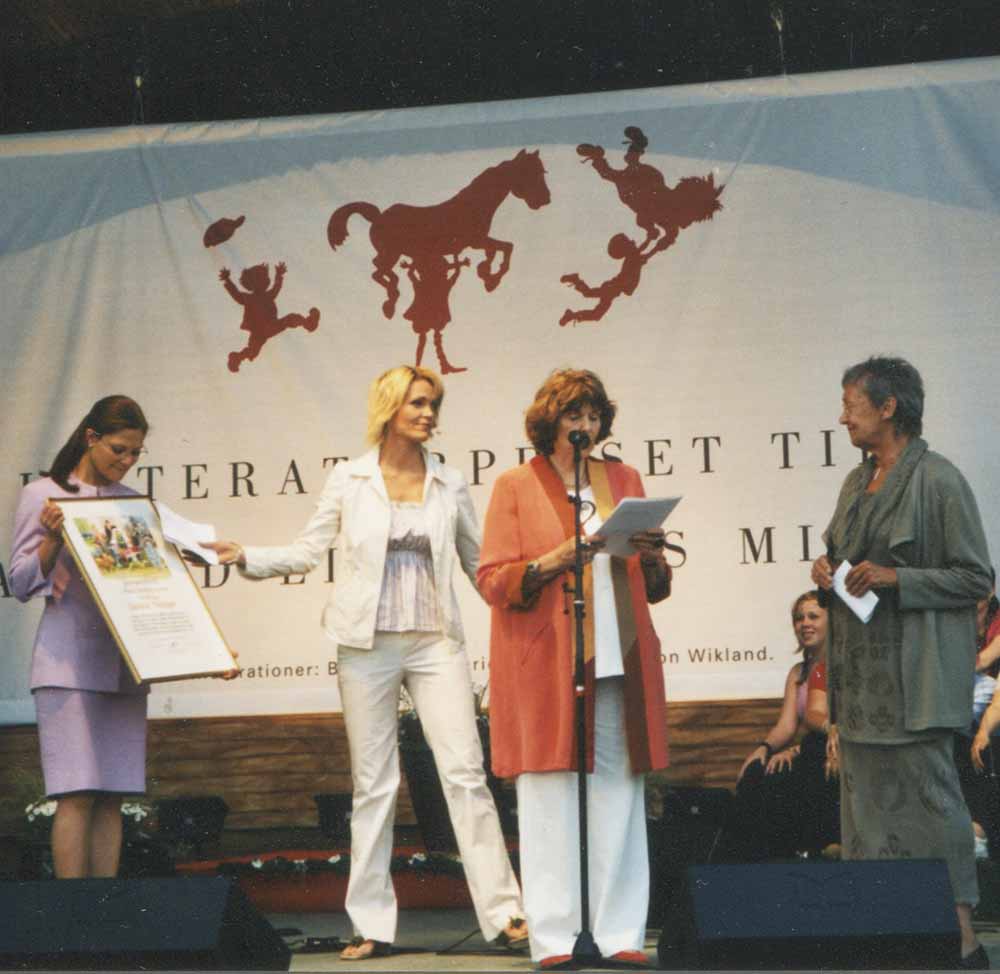

Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award

In 2003, Christine gets a call from Sweden. When she hears that she has been rewarded with the recently established Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award (ALMA), her reaction is:

“I was sitting there, quite confused, on cloud nine … I was happy, to have been praised by the jury as a ‘non-educational force with the impact of Astrid Lindgren’.”

Source: Glück ist was für Augenblicke

EN alma2

She shares this first “Nobel Prize in Children's Literature” with Maurice Sendak, an illustrator who she admires. The jury bases its decision on the fact that Christine stands unconditionally on the side of children in general and outsiders specifically. In her acceptance speech at the award ceremony in Stockholm, Christine reflects on her development as a children's book author. From being a storyteller who uses phantastic elements to becoming a realist:

“I have put down this phantastic element since many years, they are always there if needed, but for my current work not necessary anymore. Because I had understood – and this was due to Astrid’s books – that it is not the story itself, which makes children feel free, comforted and sheltered when reading. It’s the language! Language can make people smile and cry, language can comfort, can stroke, can give the feeling of shelter, it can make someone to feel free like an air balloon.”

The address can be read in full here: ALMA for Christine Nöstlinger - website

EN 2005-2018 Text

As a children’s author Christine is most often described as a great anti-pedagogue, as someone who does not want to educate children.

“We should stop to constantly form and trim children, to persuade them and let them adjust to our expectations … Let’s just watch and hear children while they are living their lives. They, already and constantly, try, with all the power they possess, to make us familiar with their way of thinking and feelings. They make up stories for us, they play for us, they are tirelessly endeavoured to let us enter their feelings and thoughts.”

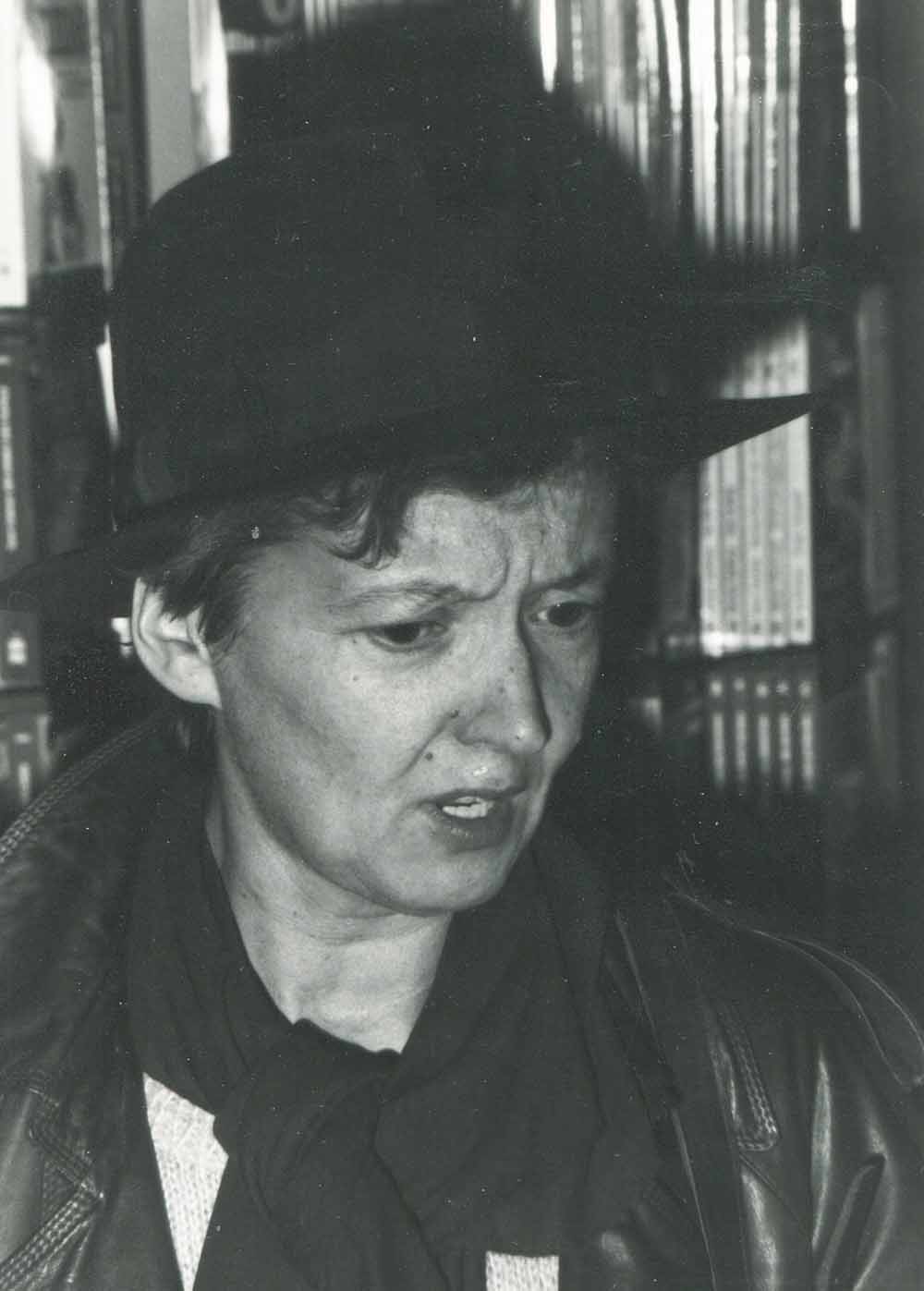

Apparently “gloriously grumpy”

Christine is admired by many for her “Viennese, dry humor” and her solidarity with people who live marginalised at the borders of society. Due to her work and her personality, she represents a moral integrity which many miss in the context of contemporary neoliberal politics.

Photo: Christine on her patio

Already achieved something

Christine represents a moral authority, reaching far beyond (children's) literature. She is often asked to comment on the prevailing zeitgeist, especially when it comes to the utopian ideas of the 70s, for example the women’s movement, and what remains:

" Well, a lot. Things like the abortion and pregnancy termination cannot be reversed today and many achievements that became regulated by the family law reform of the 70s are self-evident for women today … before you had to be married in order to stay at home with your new-born child for over eight weeks. Otherwise you didn’t have health insurance.”

A clear view

Sie sieht zwar die ihr zugeschriebene moralische Autorität mit Selbstironie („...Ich bin doch kein Guru!“), aber wenn sie gebeten wird, zu wichtigen Themen Stellung zu nehmen, nimmt sie das sehr ernst. So wird sie 2015 gefragt, im Österreichischen Nationalrat die Gedenkrede zum 70. Jahrestag der Befreiung des Konzentrationslagers Mauthausen zu halten. Sie warnt vor Rassismus und Fremdenfeindlichkeit:

EN Eine klare Sicht 2

“Vielleicht ist es ja so: Über den allgemein bekannten sieben Hautschichten hat der Mensch als achte Schicht eine Zivilisationshaut. Mit der kommt er nicht zur Welt. Die wächst ihm ab Geburt. Dicker oder dünner, je nachdem, wie sie gepflegt und gehegt wird. Versorgt man sie nicht gut, bleibt sie dünn und reißt schnell auf, und was aus den Rissen wuchert, könnte zu Folgen führen, von denen es dann betreten wieder einmal heißt: ‚Das hat doch niemand gewollt!‘"

By playing the video you agree to YouTube's terms of service.

Resignation

Auch wenn sie sich selbst als heitere Pessimistin bezeichnet, macht sie die politische Lage und der Zustand der Welt traurig. In Interviews (Quellen) erwähnt sie, dass sie sich in den 70er und 80er Jahren nie hätte vorstellen können, dass sie noch einmal eine derart reaktionäre Zeit erleben muss. Der Rechtsruck in Europa lässt sie resignieren:

„Je älter ich werde, desto weniger weiß ich Sachen. Weil ich immer mehr darauf komme, dass die Sachen, die ich früher geglaubt habe, nicht stimmen …

Ich frag mich oft, wie blöd darf man sein. Dauernd muss ich Verständnis haben, für die Sorgen der Menschen. Meistens informieren sich diese Menschen nicht, schauen nicht einmal Zeit im Bild. Es gibt doch bitteschön auch gegenüber der Gesellschaft eine gewisse Bringschuld, man muss sich informieren.“

Ageing isn’t beautiful

In her private life, Christine has to deal with ageing, illness and the loss of physical integrity since her breast cancer surgery.

In 2007, Nö suffers a severe cerebral infarction, is paralyzed on one side and loses his ability to speak. After half a year of futile rehabilitation, it turns out that he needs constant nursing care.

Christine now lives alone. She moves one last time within Vienna, to a rooftop apartment in the 20th district, close to her daughter Barbara. Nö dies in 2009.

Photo: Nö and Christine in their house in Waldviertel, Lower Austria

Ageing isn’t beautiful part2

Moreover, her own health problems start to increase, but she hardly complains. Especially not to people who are close to her. She arranges help where needed, while accepting her increasing restrictions, but retains her autonomy wherever she can.

Even if the body does not work the way it should, her mind functions very well. She concentrates on activities she likes, such as reading or solving the crossword puzzle in the weekly newspaper “Die Zeit” every Thursday.

No more children’s novels

She starts to write less, and especially less for children. Her own grandchildren are adolescents at the time and due to her age and the physical state that follows from it, she doesn’t give readings anymore. Therefore, direct contact with children is lost.

“Now, I only write when it brings me pleasure. For small children, I can still write well. For the older ones, I don’t dare to anymore. A youth book has to be written from the viewpoint of their heroes. I really don’t hold anything against those who are 13 or 14 nowadays. But I don’t understand them. The everlasting look at their smartphones …”

“Anyways, I never could’ve imagined to become 80”

In 2016, on the occasion of her 80th birthday, Christine is celebrated in Austria as well as internationally. One last time, she gives many interviews, including one in which she speaks about illness and death very openly:

“Preferably, I would live forever. On this subject, I totally agree with Elias Canetti’s, death is the greatest atrocity that one could ask from a human being. But it also depends on the circumstances. I don't feel very well, health-wise. My heart does not want anymore, my pulse has doubled, and my bones are porous. But to me, life is still quite amusing. Once it becomes really horrible, I'll find an ending. Nobody else should decide about my death. And I don’t want to bother someone else with it neither. One should be able to handle such matters personally. The only challenge is to catch the right time, as long as you still can.”

One more time in dialect

Until shortly before her death, Christine works on poems in Viennese dialect “Ned das I ned gean do warat” (“Not that I wouldn’t enjoy to be around”), which deal – among other topics – with ageing and dying.

The poetry volume is published after her death in April 2019 by Residenzverlag. Barbara Waldschütz has illustrated and graphically designed this last work.

Unfortunately

Christine dies on the 28th of June 2018 at the age of 82 years. She still managed to catch her right time. Obituaries are being sent out worldwide: NYT, Washington Post, Corriere della Sera, etc.

Julya Rabinovich in Zeit Online on the 18th of July 2018:

"A splendidly snappy and grumpy woman, whose words were usually very precisely chosen. Until her death, she did not save criticism towards the Austrian political landscape, until the end she has fought against the right wing. In a recent interview, she regretted not being able to experience the return towards the center. That sounded like giving up; it hurt me to experience this fighter being in such a mood. Unfortunately her assessment was just as realistic as her portrayal of the living conditions of her heroines and heroes – even if they could at least count on a dash of fantasy.

Sometimes I imagine that Christine Nöstlinger is still here. With flying, fire-red hair, living in an attic where she writes. Just keeps on writing. Because, as Rosa Riedl, Schutzgespenst, has said, 'If one has something as urgent to deal with, as I did back then, when one is so angry, then he cannot die properly because he can find no peace.'”